Is it okay to still love him and be hurt?

5 min read

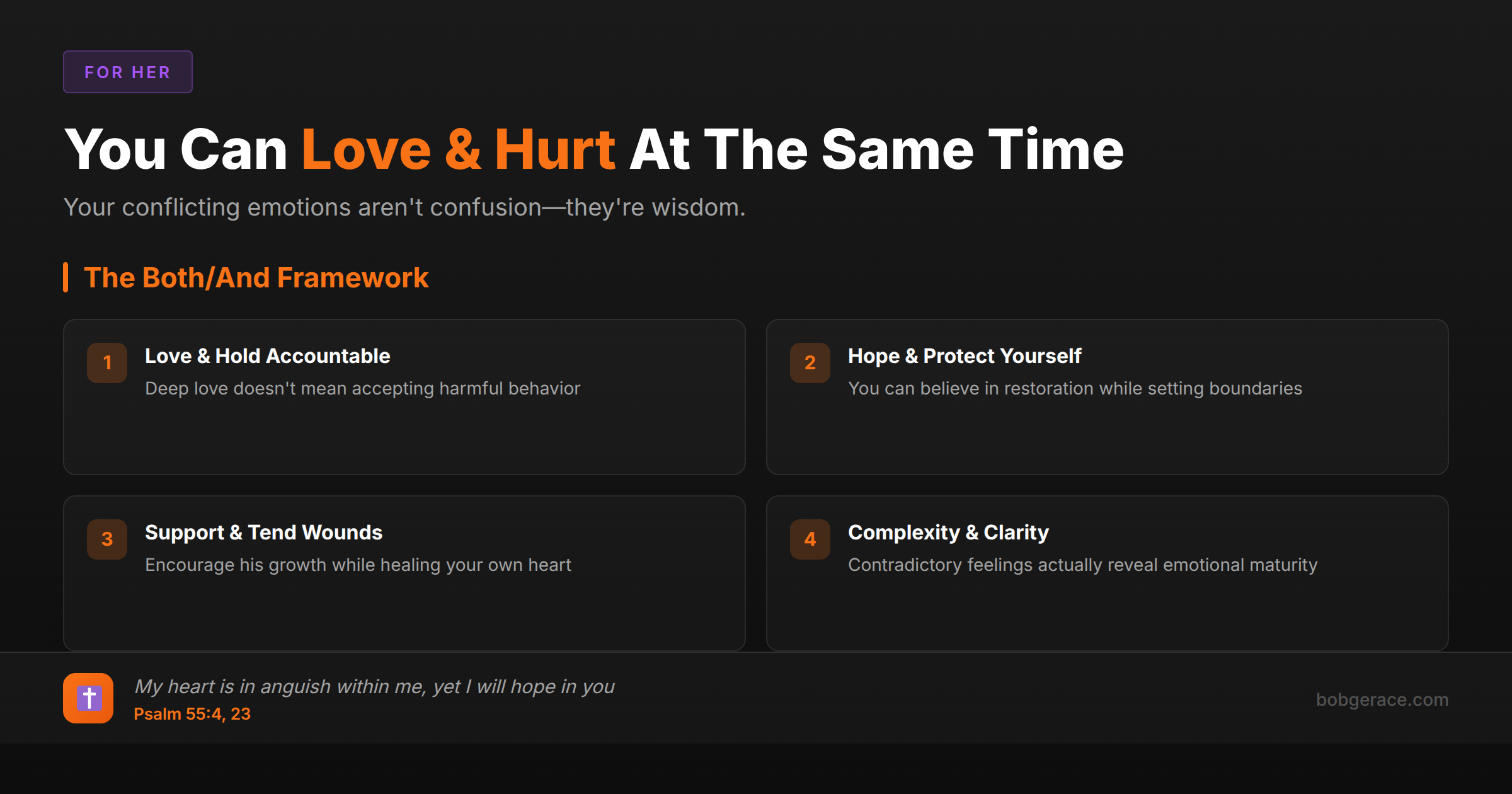

Not only is it okay to love him and be hurt simultaneously—this is actually one of the most honest and healthy responses possible. Conflicting emotions don't mean you're confused or weak. They mean you're experiencing the full complexity of deep human attachment. You love him because of years of shared history, genuine connection, and the person you know he can be. You're hurt because someone with the power to wound you most deeply has done exactly that. Both are true. Both deserve acknowledgment. The cultural pressure to pick one feeling—either 'stand by your man' or 'leave the jerk'—fails to honor the reality of long-term intimate relationships. Real love has always coexisted with real disappointment. Your ability to hold both emotions speaks to your emotional maturity, not your confusion. Many women find that acknowledging this complexity actually reduces internal pressure. You don't have to resolve your feelings into a simple answer right now. You can love him and hold him accountable. You can hope for restoration and protect yourself. You can support his transformation and tend to your own wounds. These aren't contradictions—they're wisdom.

The Full Picture

The question you're asking reveals something important: somewhere along the way, you received the message that your emotions need to be consistent to be valid. Perhaps well-meaning friends suggested you should 'just leave' or others implied that staying means the hurt wasn't real. Neither camp leaves room for the complicated truth of enduring love.

Human attachment doesn't work like a light switch. You can't simply turn off years of love because pain has entered the relationship. The same neural pathways that register his hurtful behavior are intertwined with pathways carrying memories of his tenderness, your shared laughter, the life you've built together. Your brain isn't confused when it produces conflicting emotions—it's accurately representing a complex reality.

In fact, if you felt nothing when he hurt you, that would suggest the relationship had already ended emotionally. Pain is actually evidence of continued attachment. We don't feel betrayed by strangers. The intensity of your hurt is directly proportional to the depth of your love. They're not contradictions—they're connected.

This complexity is especially important to understand right now because his transformation process will produce its own emotional complexity. You may feel hope when you see genuine change and fear that the hope will be crushed. You may feel pride in his growth and grief that it took crisis to catalyze it. You may feel closer to him after a meaningful conversation and angry that such conversations weren't happening years ago.

All of these combinations are legitimate. None of them need to be resolved immediately. Emotional healing rarely travels in straight lines. It spirals, circles back, and sometimes feels like regression even when it's progress.

The men in this program are learning to develop emotional intelligence—to recognize, name, and appropriately express their feelings. Part of that growth involves understanding that emotions are information, not commands. They're data points to be processed, not necessarily acted upon in the moment. The same principle applies to you. Your love is information. Your hurt is information. Neither demands immediate action. Both deserve acknowledgment and exploration.

What many wives discover over time is that the ability to hold this complexity—to love and be hurt simultaneously—actually positions them well for genuine reconciliation if it comes. They haven't hardened their hearts or burned their bridges. They've maintained emotional honesty that allows for authentic reconnection when trust is rebuilt.

Clinical Insight

Psychology recognizes that emotional ambivalence—holding contradictory feelings simultaneously—is not a sign of dysfunction but of psychological sophistication. Research in affect complexity demonstrates that individuals capable of experiencing mixed emotions often show greater emotional intelligence, more nuanced thinking, and better long-term outcomes in navigating difficult situations.

Attachment theory specifically explains why love and hurt coexist so powerfully. Your attachment to your husband was formed through thousands of interactions that created neural patterns of connection, security, and identity. These patterns don't disappear when hurt occurs. Instead, the brain must process contradictory data—this person who represents safety has also caused harm—which produces the mixed emotional experience you're living.

The clinical term for what you're experiencing is 'attachment injury.' Unlike general hurts, attachment injuries occur within significant relationships and involve a violation of trust at vulnerable moments. The healing of attachment injuries requires a specific process: the injured partner must be able to fully express the impact of the wound, the offending partner must take genuine accountability and demonstrate understanding of the harm caused, and new interactional patterns must replace the old ones.

Importantly, this process doesn't require the injured partner to stop loving before healing can occur. In fact, maintained attachment can facilitate healing when combined with genuine repair behaviors from the offending partner. The love provides motivation to engage in the difficult work of reconciliation; the hurt provides necessary information about what needs to change.

Research on couples who successfully navigate betrayal and restoration shows that those who maintained emotional complexity—continuing to love while also honestly acknowledging pain—often achieved deeper intimacy post-recovery than they had before the //blog.bobgerace.com/christian-marriage-crisis-desperation-weakness/:crisis. The journey through darkness, navigated together, created bonds that superficial relationships never develop.

Biblical Framework

Scripture presents emotional complexity as a consistent reality in the lives of the faithful, not a failure of faith. The Psalms alone contain stunning examples of simultaneous conflicting emotions expressed without apology or resolution—love for God alongside anger, hope alongside despair, trust alongside complaint.

Consider David, described as a man after God's own heart, who expressed the full range of human emotion without editing for consistency. In single psalms he moves from anguish to praise, from accusation to trust. This wasn't emotional instability—it was emotional honesty before God who already knows our hearts.

The prophet Hosea provides perhaps the most relevant model. God instructed him to love a wife who was unfaithful, and this love coexisted with genuine grief over her betrayal. God Himself uses this metaphor to describe His own emotional experience with Israel: 'How can I give you up, Ephraim? How can I hand you over, Israel?... My heart is changed within me; all my compassion is aroused' (Hosea 11:8). Here is the Creator of the universe modeling the simultaneous experience of hurt and persistent love.

Jesus demonstrated this complexity at the Last Supper. Knowing full well that Judas would betray Him and Peter would deny Him, He still washed their feet, still broke bread with them, still loved them. The foreknowledge of their failure didn't require the elimination of love. Both realities coexisted in the same heart.

Your ability to love your husband while being hurt by him places you in consistent company with the most emotionally honest figures in Scripture. This isn't weakness or confusion—it's the kind of complex love that reflects something of God's own heart toward His people.

Action Steps

-

1

Give yourself explicit permission to feel contradictory emotions—write down 'I can love him AND be hurt' somewhere you'll see it, as a reminder that this is healthy.

-

2

Resist pressure from others to simplify your emotions—well-meaning friends may push you toward one feeling, but your complexity is valid.

-

3

Journal both streams of emotion separately—pages for what you love and appreciate, pages for what hurts and grieves, allowing each full expression.

-

4

Notice if you're using one emotion to suppress the other—sometimes we emphasize hurt to protect against hope, or emphasize love to avoid facing pain.

-

5

Share your emotional complexity with a counselor or trusted friend who can hold space for both without pushing you to resolve them prematurely.

-

6

Ask your husband about what he's learning regarding emotional intelligence—understanding his growth in this area may help you process your own emotional complexity together.

Related Questions

Think This Could Help Your Husband?

If you believe your husband could benefit from the structured transformation process we offer, share this with him. Real change is possible when men commit to the work.

Learn About the Program →